For Better Women’s Health, Expand the ACA, Not Medicare

If the goal is expanding access and improving affordability, then building on the ACA is a better strategy.

Feb 04, 2020

May 24, 2021

Chronic Care Issues

Dr. Miller is a health care and life sciences expert. For more than 30 years, Dr. Miller has worked to improve clinical and economic outcomes by advancing the development and adoption of innovations including biopharma products, medical devices, care delivery models, clinical practices, to self-care actions by individuals. His company, HealthPolCom helps organizations create and implement programs that integrate patient perspectives with those of others to achieve multi-stakeholder alignment. His work spans, policy, advocacy, program management and communications, and he has written extensively and made many presentations about the interactions across the health care delivery, financing, research, and public health systems. Dr. Miller received his B.A. from Williams College in chemistry and his M.D. from the Yale, and has held many volunteer, non-profit board positions, and is the longstanding honorary "Team Physician" for the political satire troupe the Capitol Steps.

Full BioLearn about our editorial policies

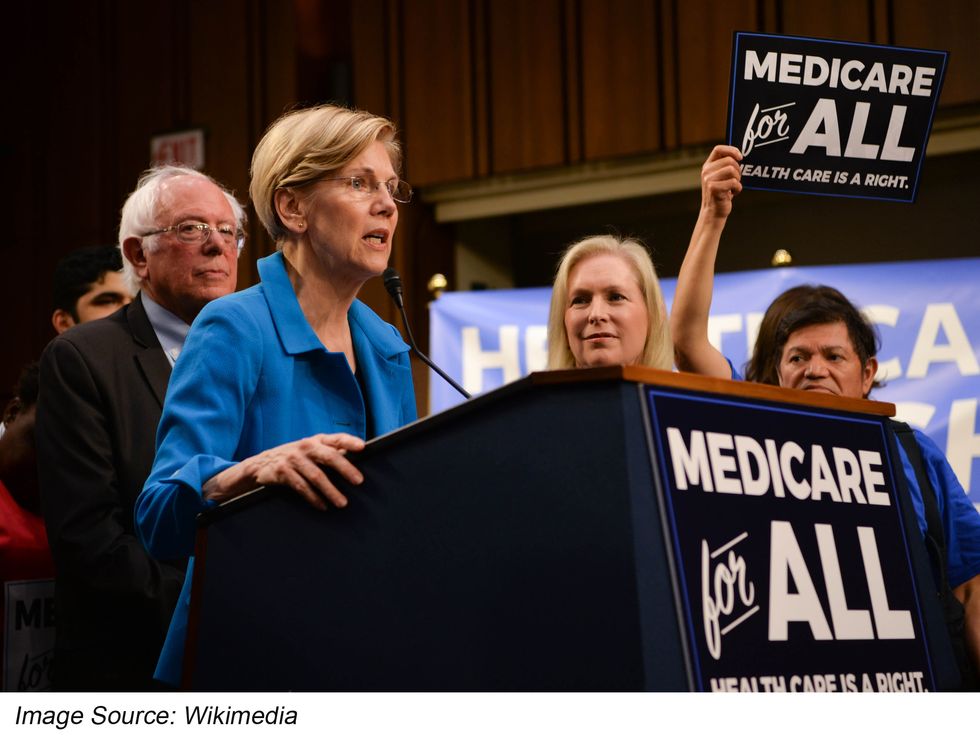

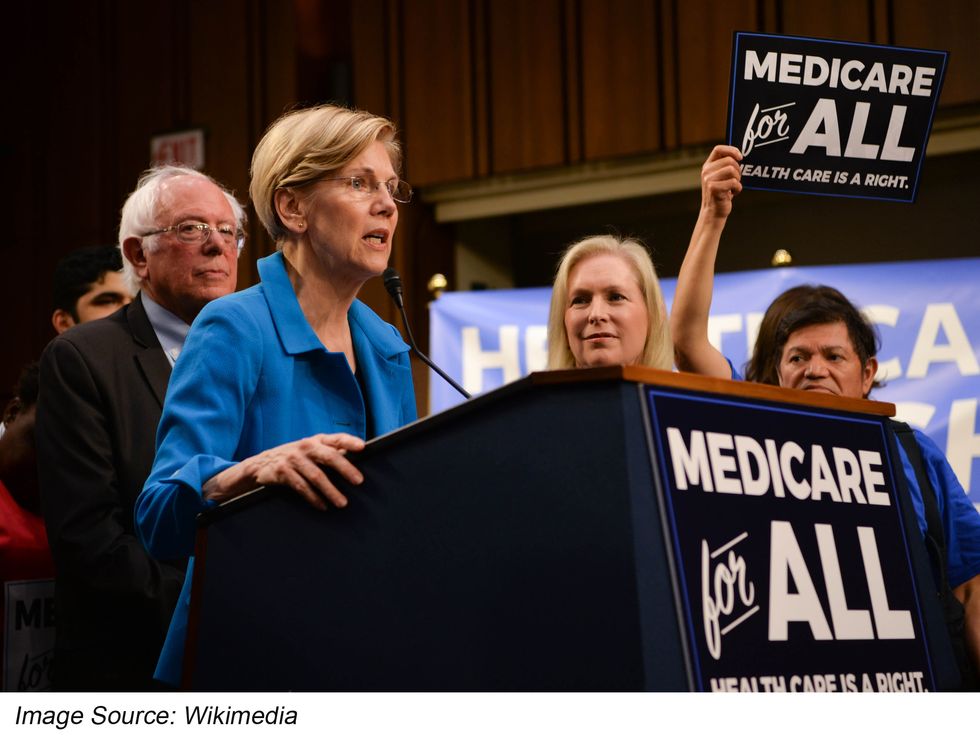

The idea of "Medicare-for-All"—or its political cousins, "Medicare-for-More" or "Medicare for all who want it"—is a popular political position this election season. But if the fundamental goals of major health legislation are to expand access and improve affordability, then they are not realistic policy plans.

The best policy to achieve those goals is building on the Affordable Care Act's (ACA) foundation for access and framework for improving affordability. Movement towards both of those goals can be done relatively quickly and inexpensively. In contrast, Medicare expansion is problematic, especially for women.

How the ACA expanded access and improved affordability

To understand why, we have to start with how the ACA changed the U.S. health-care landscape, both in terms of access and affordability.

The new law expanded access to health insurance by dramatically reducing variability among states' insurance rules and Medicaid eligibility. For example, some states allowed insurance plans to deny coverage for individuals with pre-existing conditions and permitted plans to raise premiums astronomically after someone became ill. And while some state Medicaid programs covered parents with incomes up to or over the poverty level, others only covered parents with incomes less than 30% of the poverty line. Most Medicaid programs also did not include any adults without children regardless of their income. The ACA's access provisions created more uniformity across the country, leading to about 19 million more Americans having health insurance.

The ACA also created a framework for affordability through a number of provisions, including: low-income subsidies; age-based rate banding on insurance premiums; limits on percentages of insurance company's overhead; state reviews of premiums; and tax credits. Those provisions were paired with tax penalties for some individuals without insurance or companies without coverage for employees. Those financial carrots and sticks were controversial, criticized from the right for being too generous and from the left for not being generous enough. But like the ACA's access improvements, they created more uniformity across the country.

What access and affordability means for women

For women, who generally have fewer financial resources and more difficulty paying health-care bills, the ACA's improvements in access and affordability were key. For example, the ACA resulted in about eight million more women ages 19 to 64 having health insurance, with about two-thirds of those women gaining insurance being 19 to 44-years-old.

Similarly, the ACA had provisions to improve affordability, including insurance plans being required to have an annual out-of-pocket spending limit. In contrast, traditional Medicare continues to have no limit. (Traditional Medicare currently covers about two-thirds of Medicare recipients, while the remaining one-third have Medicare Advantage plans that have limits on catastrophic costs.) A woman with significant health-care needs who has traditional Medicare and no supplemental insurance can face tens-of-thousands of dollars of health-care costs a year.

Building on the ACA may be a less rousing campaign sound-bite than expanding Medicare, but it makes for better policy, particularly for people who need extensive or specialized care. In contrast, expanding Medicare would direct time and resources from restoring the ACA's gains that seem to have eroded over the past few years, with several million fewer people having health insurance, many of those being children.

Ignore the deficit at your own risk

The country's growing deficit means that health-care policies are inexorably tied to fiscal concerns and policies. That reality is often ignored in political and campaign contexts and statements.

Significantly expanding Medicare could increase federal spending by $20 trillion over 10 years, according to Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), and possibly up to $34 trillion according to the Urban Institute and the Commonwealth Fund. In contrast, different ACA improvements would cost $300 billion to $1.0 trillion over 10 years, according to the same source.

The relatively high price-tag for "Medicare-for-All" would likely require higher taxes and therefore generate strong political headwinds.

Of course, Medicare-for-All advocates, including Senator Warren, have argued that even with increased taxes, the average costs of health care for Americans would decline. But such statements hide the uneven distribution of health-care costs.

Specifically, 5% of people in any group are responsible for about 50% of costs, a long-standing distribution that was recently documented by the Kaiser Family Foundation's analysis of 2016 data. So the majority of Americans (who use less than the mathematical "average" amount of health-care services) would likely see higher overall combined health-care and taxation costs.

Don't play with health care

Thirty years of working on health policy has taught me that perfect is often the enemy of the good. Big changes involve big risks. While it might make sense to take such risks in other ventures such as space travel, in health care, the stakes are higher. The outcomes affect far more people, most of whom have little input into how the system operates.

Like many readers, I have personally experienced the consequences of such risks. Before the ACA became effective in 2014, I was denied health coverage due to minor preexisting conditions. I've talked with many people who couldn't get health insurance or afford care for themselves or their family members. I know that achieving something good sooner is a better and a more morally responsible path than waiting for the hypothetical "great" solution. As Joe Biden famously said to Barack Obama during the signing of the ACA, this is a "big f***ing deal."

On the positive side, there may be more underlying bipartisan support for ACA improvement than for Medicare-for-All. For example, Republican governors such as John Kasich of Ohio and Jan Brewer of Airzona embraced—and even fought for—Medicaid expansion, while other GOP governors such as Maryland's Larry Hogan and Massachusetts' Charlie Baker have supported the broader ACA benefits for their states. In addition, I know former Republican health-care congressional staffers who have publicly talked about why the ACA needs to be repaired, improved, or stabilized. Their specific recommendations for change may differ, but they are all promoting pragmatic policies that benefit Americans.

Advocate for realistic change

Women's health is not, or should not, be a partisan issue. Those who support improving women's health should focus on identifying the candidates—Democrat or Republican—whose policies aim to increase access to health insurance and health care; make health care and prescription drugs more affordable; and support research and initiatives to improve women's health in the future.

Women's health supporters can start by questioning candidates on how she or he would turn campaign promises into realistic initiatives. Don't be swayed by vague promises such as "everyone will have access to any doctor they want," "there will be no premiums or deductibles," or "prescription drugs will be free." Such statements sound great, but are too good to be true because they aren't real—they are fiction.

Medicare-for-All—or some version of a "single payer" system—may yet become reality in the U.S., but most likely as part of the ongoing evolution of the U.S. health-care financing system. In the meantime, stepwise change up a manageable slope is a better path than banging on the wall without effect for years or decades with the hope that eventually a door will open revealing a bridge leading to a visionary future.

People with real health-care problems today need solutions as soon as possible. Americans don't benefit from ideas that look great on campaign signs but don't lead to better care, more access, or improved affordability. Positive change is possible, but it begins with realism.